Analytics is not about data. It's about truth.

Or, at least, it should be.

Analytics teams fit awkwardly into businesses. We’re the spokespeople for quantitative data, in a world where quantitative data isn’t always critical. And the repercussions of this misfit can be painful: we struggle to weave our insights into places where they don’t belong, we’re too often relegated to providing data as a quiet backdrop (dashboards) in strategic conversations. Sure, when our business counterparts hunger for our slant on things, we become magically impactful. But at other times, we get stuck in loops where we’re seen as SQL mechanics, we’re ignored as the overly-pedantic rigor police, and our doses of insight seem to fall on deaf ears. We have some bad habits, for sure — we lack resourcefulness and flexibility, business acumen, proper tooling, certainly. But I don’t believe these are symptoms, not diagnoses.

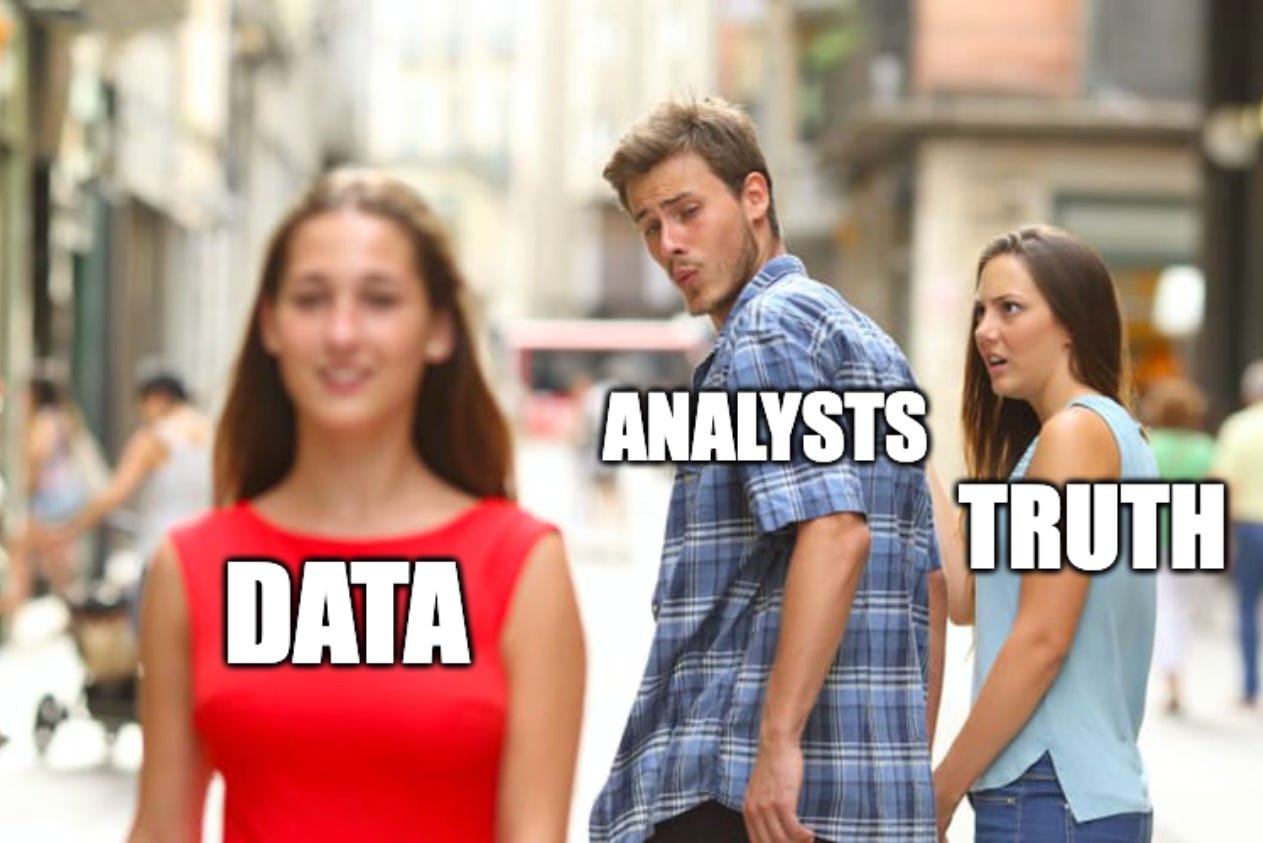

In my opinion, our shortcomings point to a fundamental misconception: that analytics is about finding data, when analytics should be about finding truth. And everything else can follow. We should value clarity of thought, not precision of measurement. We should value removal of bias in all forms, not just in our small-minded efforts towards eking out statistical significance. We should pursue logical clarity and good choices, not beating our stakeholders with asterisks and scientific pedantry.

We need to be truth-seekers, not data deliverers, and our greatest, most valuable contribution is to simply fight the endemic dominance of bias and baseless certainty in decision-making, goal-setting, strategy. Or perhaps that’s a pipe dream, but let’s see how far we can take it.

The dual curses of the business world

The business world is rife with two dangerously symbiotic scourges:

Personal agendas (bias)

Fake it ‘til you make it (baseless certainty)

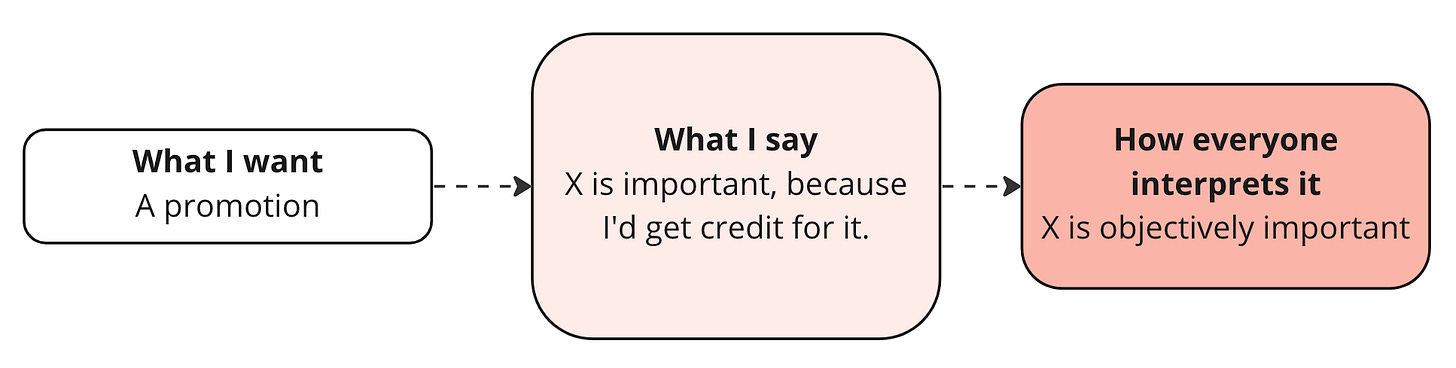

We are all biased, of course, and so it’s unsurprising that our personal agendas might infiltrate our work. But arguments tainted by bias are too often presented with unfounded certainty — a desire to win overwhelms our desire to seek understanding. And when the Machiavellian (“I want a promotion”) masquerades as authority (“WE SHOULD DO X”), it becomes impossible to distinguish truth from self-interest.

So how does analytics fit into this tomfoolery? Well, businesses have a bias problem. Yet we understand bias. So why don’t we make our charter to solve that problem? Our incentives are aligned here: the corporate bias-certainty flywheel nullifies analytics — if your insights, your analyses, your best data-driven wisdom are placed in a context of ambiguous, invisible objectives and opaque reasoning, your insights are being shipped to the void.

Analytics is not about data

But accession can’t happen without the death of the monarch. Before we can establish a new charter—before we discuss explicitly what analytics should be—let’s briefly talk about what analytics should not be. And as much as it might seem self-apparent that analytics should be about data, it should not, and to date, this has been our first and biggest mistake.

Data is our substrate, but not our direct value-add. Consider a common trope in data circles over the last few years: it’s not about data, but about insights. Taken further, it’d follow that interpretation, therefore, is crucial, far beyond the herding of raw data alone (cooking isn’t chopping). And taken to the logical extreme, data is actually a small part of the story — yes, it’s useful on its own, but that is not where our value comes from. Data can mean anything, after all.

And even if we shift our focus from curation to interpretation, this still isn’t quite right. We are not our deliverables — we need an objective, not a format. A credo, not a series of baseless rituals. If we don’t start with the right objective, we will ultimately advance the wrong one. Plausible placeholders often fill this gap: “storytelling” which is just as likely to be helpful as misguided; “statistical rigor”, which is just as likely to lead to better thinking as it is trap decision-makers in arduous and unnecessary pedantry.

Our objective should be truth

So what should our objective be? In my opinion, truth.

We live in a world where bullheaded confidence in the face of ambiguity are valued above all else — and this, coupled with the bias inherent in us all (intentional or not), advances a broken ecosystem of decision-making and strategic planning. An ecosystem in which the most heeded voices are the loudest, and “done is better than perfect” becomes an excuse for systemic self-deception.

And we — WE — are best positioned to fight this. We are trained to look at data (quantitative or otherwise) and interpret it objectively, and if we want to leverage our skills to their fullest, we need to interpret and guide strategy outside of our little quantitative worlds. We need to be the best at synthesizing arguments, assumptions, hypotheses, and data to help decision-makers chart a path through ambiguity. We need to shape the information environment in a way that resists fallacy and lends itself to better decisions, better actions, better goal-setting. We need to constrain and map the idea maze, not introduce our own bias into it.

And it’s not just that data requires interpretation. Yes, data can mean anything. But anything can mean anything. We are far too comfortable in our little holes, pursuing intellectually rigorous projects within scopes we can control. We cull problems, firstly, according to how suitable our methods or to them, rather than rank ordering them by importance. Perhaps it’s even our inherent selection bias — we seek out projects that we can deterministically solve. But the corporate world is messy, and we’re missing value in our attempt to maintain intellectual purity.

Off my soap box: I recognize this is probably a pie-in-the-sky dream, far beyond what we might be reasonably able to attain. On the one hand, solvable data problems are often more satisfying than the intractable business / interpersonal ones. And on the other, who knows if we can even shape incentive structures and perception so we’re valued in this way. But just… consider the mindset shift. If you aim to be the most unbiased, valuable voice in a room—rather than the most quantitative—I guarantee you’ll be more unbiased, and more valuable.

A final point: while this is certainly a lofty goal, a baby step you can take is to give narrative—not data—primacy. We’ve built Hyperquery for this purpose. Obviously, the mindset problems need to be solved here above all else, but check us out if you want to get nudged in the right direction. 🙂