Why I love diagrams, and you should too

They help you think, and help you help others think

I am known internally at Hyperquery for making diagrams. I make diagrams of everything. Hell, if you’ve ever talked with me, you probably know I love making diagrams.

I’m here to explain why I make so many diagrams, and help you start on your diagram-making journey.

👋 Hello! I’m Robert, CPO of Hyperquery and former data scientist + analyst. Welcome to Win With Data, where we talk weekly about maximizing the impact of data. As always, find me on LinkedIn or Twitter — I’m always happy to chat. And if you enjoyed this post, I’d appreciate a follow/like/share. 🙂

For once, this isn’t a direct post about data. But it is a post about persuasion, which is a requisite skill in making data useful. I’m cross-posting this on a substack where I’ll put data-unrelated writings — subscribe there if that sounds interesting!

The case for diagrams

Prose is limiting. It’s unstructured, so you have to rely on the reader to recreate a faithful representation of that concept in their own heads. Of course, this means you can craft boundless narratives, stories, imaginations — this makes text the perfect medium for storytelling and rich context-setting, where the reader’s mental representation is not just one of concepts or facts, but one of emotions, imagery, nuance. But it’s a poor medium for clearly depicting concepts and the relations between them.

Diagrams, on the other hand, enable you to augment your ideas with additional spatial information, which will reinforce comprehension. Take, for instance, the following diagram. You can see both a line of prose explaining the idea of these two paragraphs, as well as a diagram of it. But note that the diagram solidifies the spatial information in way that the prose just can’t (at least, not without a lot of painstakingly careful writing).

That said, certainly you need prose at times (this section body was useful, no?), but diagrams can provide a dimension of information conveyance that text simply can’t.

Types of information that diagrams can reinforce

There are four axes by which I’ll usually relate entities spatially:

Hierarchy

Sequence

Proportion

Color

Let’s walk through some examples of each.

Hierarchy

Hierarchy allows you to place emphasis on one thing above another. There are a number of ways to do this. You can use subordination, where elements are subsumed within other elements. You can stack objects, as in a pyramid. You can even just use the vertical axis subtly, and folks will naturally perceive things at the top are more important.

Sequence

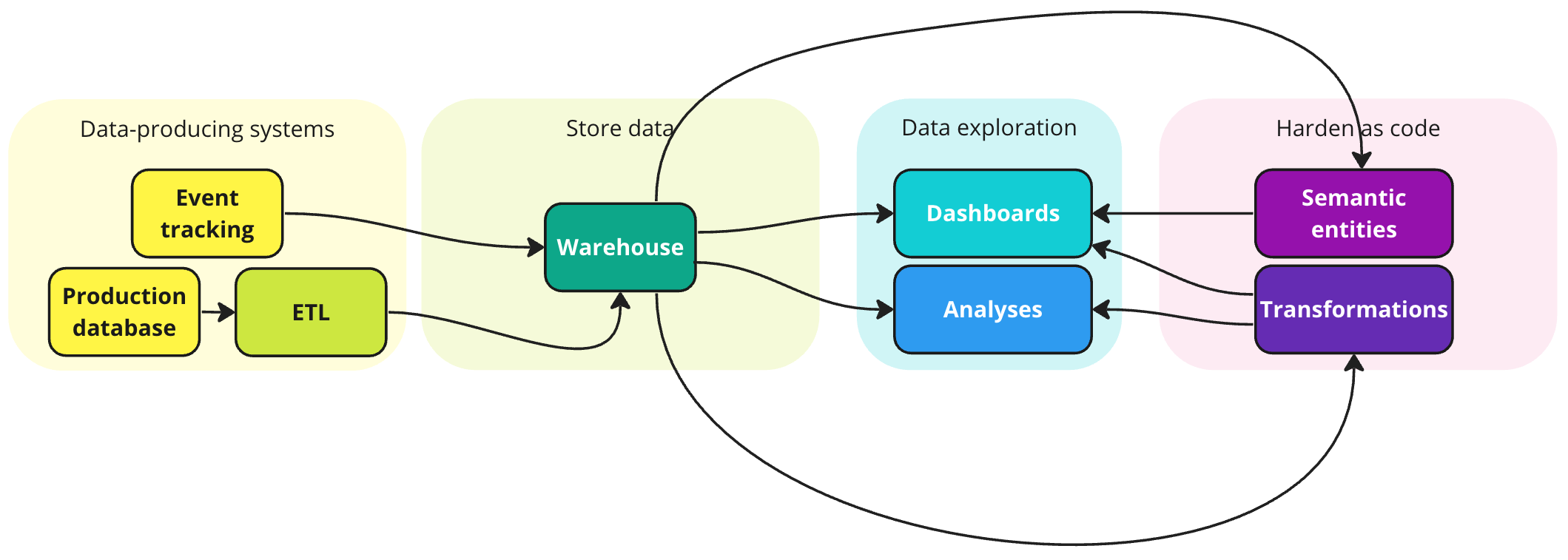

Sequence allows you to hint at directionality. There are two ways to show sequence: explicitly, through arrows, or implicitly, through general left-to-right orientation. An example that contains both of these is shown below: when I was first trying to understand how data tooling in corporates worked, I wanted to use a single diagram to understand two different sequences and how they were related:

The order in which companies usually buy data tools. (shown by the sequence of left → right boxes, below)

How data flows through that system. (shown by the black arrows)

Notice how having these two in the same place helps clarify the relationship between the two flows in a way that would be extremely cumbersome to lay out in text.

Proportion

Elements in diagrams have size. By showing certain things as bigger or smaller, especially when used with hierarchy, can convey importance.

In the below example, I show a central object — mindfulness — and the hormonal soup of effects that get in the way of it. By making the central component bigger (and a different color, and the positioning), it’s obvious that this central box is of primary importance, while the others are secondary attributes.

Color

Color is powerful — it enables you to link concepts to each other in a way that is spatially unrestricted. A couple of warnings are warranted here, however. First, make sure you have a legend when the colors mean something. Second, if you’re using colors to link together different concepts, try not to over-use color, particularly when objects are far from each other. Too much color information can overloading your audience with information. The only exception is if you’re using color as a gradient to indicate magnitude or simply to distinguish / accentuate other spatial information

In the above diagram, I’m trying to make the point that, while data is the most important building block in the DIKW pyramid, the pyramid should be inverted when viewed from the vantage of importance. I associate color with text to reinforce the link between the two pyramids, reducing the cognitive load to figure out the relationship between the first pyramid and the second. By contrast, notice how unconvincing the below, colorless diagram is.

Combinatorially

The final point I’ll make is that you don’t need to — or rather, you shouldn’t use these in isolation. They can be extremely powerful when used in conjunction, especially when you’re dealing with heavy concepts with heavy sub-concepts. Diagrams can organize the mess of information that you’ve laid out in a doc spatially, making it easier to keep track of a large number of points.

For instance, when I first started Hyperquery, I wrote out a root cause diagram of the pain we’re solving. This is nearly intractable, even as a diagram, but imagine trying to build this causal graph through conversation and text — it was an absolute nightmare. You get lost traveling down forks and side-arguments, and you have to give yourself a lot of time to let your brain naturally unravel the multiple trains of thought. This, at least, gives you a full view of the complexity, and, as a result, a clearer way to traverse the arguments without getting lost along the way. I use color to differentiate between problems, root causes solvable by tools, or root causes unsolvable by tools. I use arrows to link the mechanisms together. And I use size to keep the emphasis on the most painful problem — that “analysts are treated like SQL mechanics”.

How diagrams can help you

The benefits I’ve noticed are threefold:

Diagrams can help you navigate ambiguous problems.

As in the above Hyperquery root cause diagram, often seemingly simple problems are attached to a mess of different sub-problems. Being able to lay these out and sift through them efficiently.

They can help you structure your understanding of the world.

As in the “Modern data stack and modern data flows” diagram, a diagram can help you lay out your understanding of complex spaces, giving you a better vantage from which to view a very complex problem space.

They can make you more convincing.

Diagrams provide a secondary axis of information delivery that can help transfer nuanced ideas to others. This is why infographics and videos are so powerful. But diagrams let you leverage that power without a lot of extra work.

At this point, hopefully I’ve convinced you that diagrams are the best. If you want to get started, here are a few tools that I like to use:

Pen and paper free

The best, tbh.

Excalidraw free

Free but not as ergonomic as other modern tools. Integrates really nicely with Obsidian, however.Miro paid

The gold standard, particularly in that the amount of time it takes to get something that looks great is extremely low. But poor organization systems.

Whimsical paid

A full-on workspace. The ability to add diagrams to documents is cool. Great for collaboration, especially when you need to mix prose with diagramming to make sure context is easy to share across your team.

Alright, that’s all for now. Tune in next time for more regularly programmed data writings.